A Drug’s Convoluted Journey from Factory to Patient

The warped incentives and mysterious middlemen that broke the pharmaceutical supply chain

Prescription drugs in the US are extremely expensive. Everybody can agree with that.

Who is to blame for the high prices? The answer to that is a bit more convoluted.

There are many players involved in the development, distribution, and pricing of prescription drugs. In this article, we walk through the entire journey of a prescription drug pill — from it being created in a manufacturing site to a patient receiving it.

The high-level steps for a pill to get from the manufacturing site to a patient are:

Pills are created in a drug manufacturing site

Transferred to the wholesale distributor

Stocked in retail, mail-order, and other types of pharmacies

Prices negotiated and claims processed by a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM)

Dispensed by pharmacies to patients

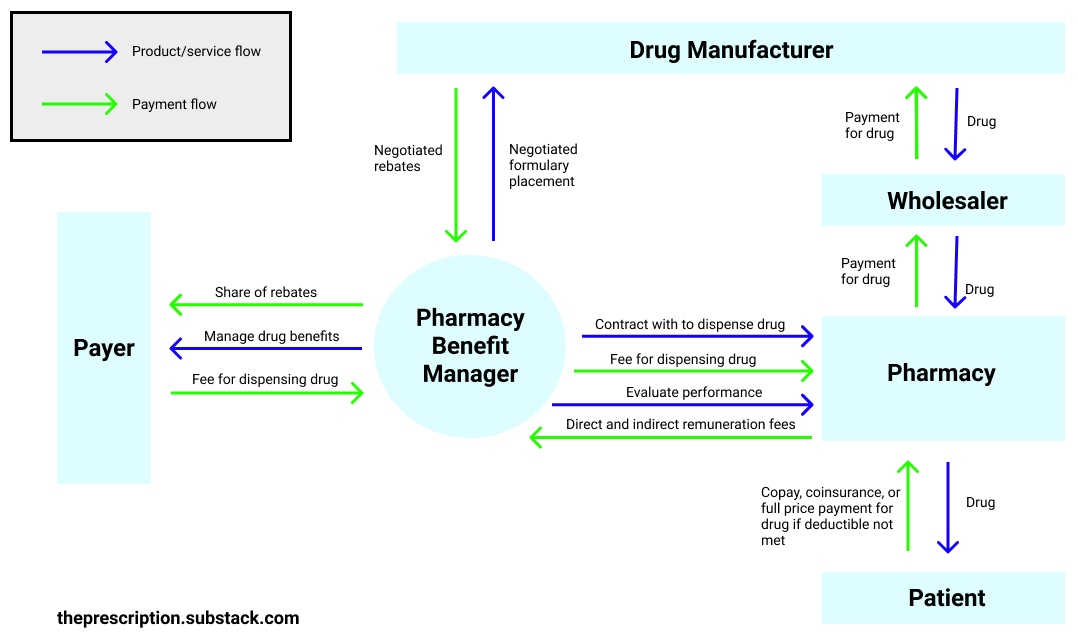

Overview of the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

Let’s dive into this process in a bit more detail. First, the drug manufacturer creates the drug and sets its list price. Since the US has no caps on drug pricing, the manufacturer has broad leeway in setting the list price. Let’s say that for Drug A the manufacturer sets the drug’s list price at $100. The wholesaler would then buy Drug A from the manufacturer. Usually they buy in bulk and thus get a small discount (i.e. they pay $98). Then, the pharmacies would buy Drug A from the wholesaler for a small premium (i.e. $100). This takes care of the supply side for drugs but where does the demand come from?

You would think that the patient would just buy the pill from the pharmacy and the insurance company would pay for it. And that is how things used to work: every time a patient filled a prescription at the pharmacy, the insurance company would process the claim and pay for the pill.

However, in the late 1960s, the insurance companies began expanding drug coverage and quickly got overwhelmed by the amount of paperwork they had to do to handle all of the claims. The pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) role emerged to fill this need and take the messy work of processing prescription drug claims off of the insurance companies’ hands. In the 1970s and 80s, when drug spending began to spiral out of control, PBMs expanded their role to use their massive negotiating power and expertise to secure better drug prices from drug manufacturers. Payers were happy to hand this role over to the PBMs since very few payers had the leverage or expertise to be able to negotiate the prices of thousands drugs by themselves.

The role of PBMs has significantly increased since then. PBMs are the ones who decide which drugs you can get at the pharmacy and how much you pay for them. They do this by managing prescription drug benefits on behalf of insurance companies, employers, Medicare Part D drug plans, and other payers. They negotiate drug prices with manufacturers as well as negotiate and process reimbursements for dispensing drugs with pharmacies. They also evaluate the performance of pharmacies. Let’s look at each of these functions in more depth.

Price negotiations and rebates

PBMs negotiate lower drug prices with manufacturers by securing rebates. For example, a PBM could negotiate a 40% rebate on Drug A. This means that every time Drug A is sold (which normally costs $100), the drug manufacturer will refund $40 to the PBM. The PBM is then supposed to pass this $40 refund back to the payer. The payer is supposed to pass the $40 refund back to the patients in the form of lower premiums the next year. Through this passing back of rebates to the payer and the patient, the PBM is supposed to be lowering drug prices.

However, it’s a point of debate how much money the PBMs actually pass back since the PBMs carefully guard what rebates they have secured. For example, the PBM could negotiate a $40 refund from the drug manufacturer and only pass $20 of it back to the payer. The PBM would pocket the rest of the $20 and no one would know!

Why do drug manufacturers even give these rebates? Because, in exchange, drug manufacturers want preferred drug placement on the formulary. The formulary is a list of generic and brand name drugs that are covered by a health plan. The goal of the formulary is to encourage patients to use safe, effective, and affordable drugs. This is accomplished by having different tiers in the formulary, each with different patient cost-sharing structures.

For example, a three-tier formulary could have 5% patient coinsurance for generic drugs, 20% coinsurance for preferred brand drugs, and 40% coinsurance for non-preferred brand drugs. This means that for a drug with a $100 list price, the patient would pay $5 if it is a generic drug, $20 if it is a preferred brand drug, and $40 if it is a non-preferred brand drug. In closed formularies, the non-preferred brand drugs are not covered by insurance at all.

The lowest tiers are supposed to have the safest, most effective, and most affordable drugs. These tiers have lowest patient cost-sharing — which means that the patient has to pay less out of pocket to buy the drug — to encourage patients to buy more of these types of drugs. However, since drug manufacturers want to maximize the number of pills they sell, they offer PBMs huge rebates to get their drugs placed on these lower tiers (their “preferred drug placement”) even if their drugs aren’t the safest, most effective, or most affordable.

This has created an unfortunate “pay-to-play” dynamic, where drug manufacturers need to pay PBMs massive amounts of money through rebates in order to get their drugs onto the formulary and even more to get onto the lower tiers of the formulary. Drug manufacturers selling expensive brand drugs can afford to pay a lot in rebates while manufacturers selling cheaper generic drugs can’t. Thus, more expensive, less effective drugs may end up being covered by payers while cheaper, more effective drugs may not.

The mechanic of the drug manufacturers having to give the PBMs rebates, in turn, causes the drug manufacturers to increase list prices to compensate. Researchers found that, on average, every $1 increase in rebates was associated with a $1.17 increase in list prices. The PBMs are happy with these list price increases because their rebates (which are usually a percentage of the list price) go up. However, since the patient’s coinsurance is also based on the drug’s list price, the out of pocket price of the drug for the patient also goes up.

Middleman fees and spread pricing

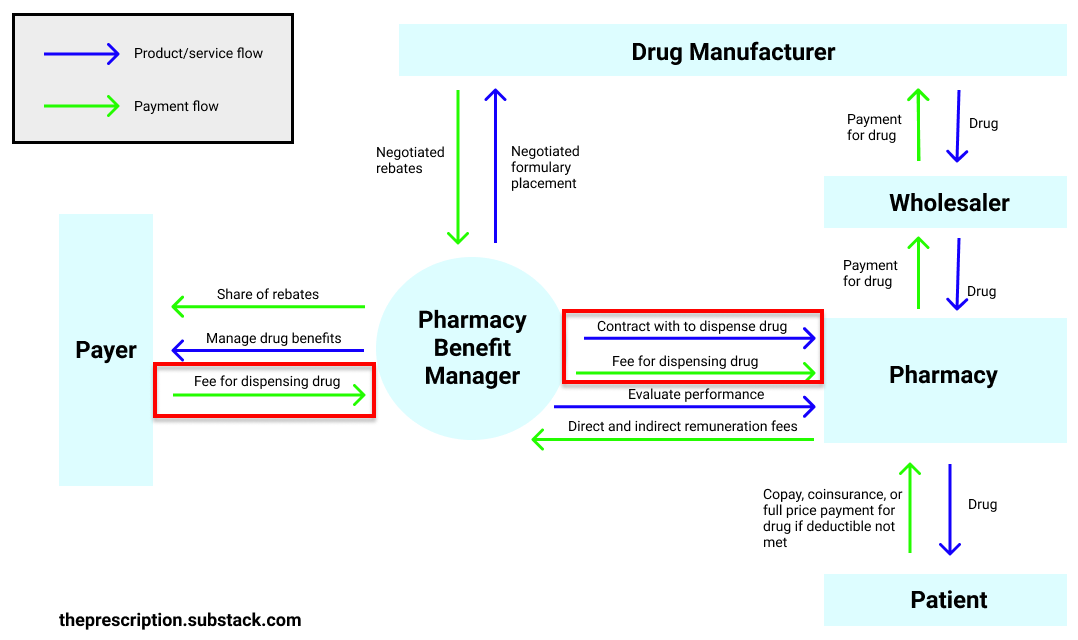

PBMs also handle contracting with pharmacies to dispense pills and reimbursing them for it. Then, the PBMs invoice the payers for the dispensing of the pill.

You would think that this would be a straightforward transaction: the PBM pays the pharmacy $95 for dispensing Drug A so the payer pays the PBM $95. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. (The PBM only pays the pharmacy $95 instead of the full cost of the drug because the patient pays the pharmacy rest.)

The PBM, being the middleman, can pay the pharmacy $95 for dispensing Drug A, invoice the payer $130, and pocket the difference. This difference is called “the spread” and is supposed to be the PBM’s administrative fee.

Understandably, PBMs should get paid for their work and you would expect the PBM to take a few dollars’ administrative fee per pill dispensed. However, the spread charged can be egregious at times — in some cases, payers were paying their PBMs 5 to 20 times more than what the PBMs were paying the pharmacy to dispense the same pill.

To get a sense of how bad the spread pricing can be, look at this real-life confidential document that shows the spread between what the PBMs are charging and what they are paying out:

As you can see, in many cases, the PBM charged the payer over $100 and paid the pharmacy nothing (the patient’s copay covered the cost of the drug). For Fluocinonide Cream, the PBM got to pocket over $2,000 every time that pill was dispensed. This spread pricing means that payers are paying more per drug, with the PBMs pocketing a lot of the money. And the payers are passing these costs onto patients via higher premiums and taxes.

Pharmacy quality evaluation and remuneration fees

Lastly, PBMs evaluate pharmacies on different quality measures and take direct and indirect remuneration fees (DIR) if the pharmacies don’t meet the targets. Months after a pharmacy has dispensed a pill and the patient has already taken it, the PBM can come back to the pharmacy and claim that the pharmacy didn’t meet certain performance guarantees. Then, they take back some of the money that they had paid to the pharmacy.

However, according to an investigative piece in Axios by Bob Herman, a whopping 99% of pharmacies incurred penalties. This is partly because pharmacies are being measured on criteria that they have little to no control over and the data used for evaluation is often incomplete. For example, pharmacies are often measured on whether their patients adhered to their medications. Unfortunately, the calculations are based on claims-level data, which doesn’t capture the entire story. For example, if the patient decided to pay with cash instead of using their insurance or the doctor changed their prescription, the pharmacy may get dinged for the patient not adhering to their medications when, in fact, they might have.

Why do PBMs get away with all of this? Because of the complete lack of transparency in the system — no one actually knows how much the PBM is making through rebates, spread pricing, and DIR fees. And there have been many active efforts to keep this obscurity in place — for example, gag clauses in many pharmacists’ contracts prevented them from sharing with a patient that an equally effective and less expensive drug option existed. Fortunately, the Senate voted a couple of years ago to ban these gag clauses.

Consolidation

The consolidation in the PBM market has further increased the existing PBMs’ market power. The top three players — Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx — handled 76% of prescription claims in 2018 (and it’s only gone up since then).

There has been consolidation between PBMs and payers as well — Aetna now owns Caremark, Cigna owns Express Scripts, and UnitedHealth Group owns OptumRx. In theory, the payer owning the PBM should cause the PBM to negotiate lower prices. Payers want to lower their costs so the PBMs should prioritize lowering drug costs instead of prioritizing increasing their rebates earned (which doesn’t necessarily lead to lower drug costs).

But, in reality, often the opposite can happen. PBMs generate more revenue and are more profitable than insurance companies — Aetna, in 2017, reported $60.5B in revenue and $1.9B in profits while its PBM business, Caremark, generated a whopping $130.6B in revenue and $4.8B in profits. Thus, oftentimes, instead of the payer’s incentives dictating strategies, the PBM’s incentives dictate strategies instead.

PBMs have also begun owning their own pharmacies. They can then force patients to only use the PBM’s mail order services or only fill their prescription from the PBM-owned pharmacies. This increases the PBM’s revenue — since the PBM is getting additional revenue from actually filling prescriptions — but makes it harder for independent pharmacies to compete and for patients to fill their prescriptions from wherever they want.

GoodRx

GoodRx has been able to take advantage of this broken system and create a product — a tool that provides patients with discounts on drugs — that benefits both patients and many other players in the drug supply chain.

GoodRx works by focusing on cash pay transactions for drugs. These are transactions for drugs that aren’t covered under insurance — either because the patient doesn’t have insurance or the patient’s insurance doesn’t cover the specific drug that the patient needs. In these cases, the patient has to pay the full retail list price that the pharmacy has set. These retail list prices are inflated since PBMs will not reimburse a pharmacy over their retail list price. Thus, pharmacies typically establish extremely high retail list prices that exceed the maximum expected reimbursement from any PBM.

But, if you are a patient paying without insurance, you are forced to pay this arbitrarily high retail list price. Many patients end up not being able to afford paying the full price and thus choose not to fill their prescription at all. This ends up hurting many of the players in the system:

Patients can’t afford to pay for the full-priced drug and thus choose at times to not fill their prescription

PBMs are unable to tap into this cash pay market (since PBMs only handle claims for drugs that are covered under insurance)

Providers can’t help their patients find drugs that they can actually afford to take

Pharmacies can’t lower their retail list prices without the PBMs lowering their reimbursement rates. GoodRx solves all of these players' unmet needs by offering patients access to the PBMs’ lower negotiated rates in the form of a coupon. For example, if the pharmacy set the retail list price of Drug A to be $300 and your insurance didn’t cover Drug A, you would have to pay the full $300. But say a PBM had negotiated with the pharmacy a $110 price for dispensing Drug A. Now, using GoodRx’s coupon, you would get access to the PBM’s lower negotiated rate and pay $110 instead. Every time you use the GoodRx coupon, the PBM whose negotiated rate you used would get paid a transaction fee and a portion of that fee would go to GoodRx.

With this new system, patients are able to get access to drugs at low costs, PBMs can collect transaction fees on drugs they couldn’t previously, and providers can help patients find drugs that they can afford. The pharmacies aren’t too happy with this system since patients are paying the discounted price now instead of the full price for drugs. However, since patients can just go to another pharmacy if one pharmacy doesn’t accept GoodRx’s discount card, pharmacies have no choice but to accept the card.

Sometimes the deal that you can get with GoodRx is even better than what you can get through paying with your insurance. Why? Because GoodRx partners with multiple PBMs and gives you access to all of their negotiated rates. So if another PBM has negotiated a better rate than your PBM, you can access that better rate through GoodRx.

Amazon Pharmacy

Recently, Amazon announced their own pharmacy service. It’s essentially the same offering as GoodRx (where they provide discounts on drugs by providing patients access to the PBM negotiated rates) and a mail-order pharmacy combined into one.

Since the market for offering discounts on drugs is pretty limited (GoodRx makes around ~400M in revenue per year, which is chump change for Amazon) because it can be only used when patients are not using their insurance, it’s likely that Amazon is just offering the discounts on drugs as an additional benefit for Prime members to make members less likely to churn. The real money-maker for Amazon will be their mail-order pharmacy.

Reforms

As you can tell, the pharmaceutical supply chain is quite broken. PBMs are making huge profit margins through rebates, spread pricing, DIR fees, and other revenue streams with little transparency or oversight.

There have been many reforms suggested to fix this system. Some of them are:

Enforce increased transparency

This would require PBMs to disclose the rebates they have negotiated with the drug manufacturers and what percentage of that rebate they have passed back to the payer. It would also require PBMs to disclose the amount of spread, or the difference between how much the payer is paying the PBM and the PBM is paying the pharmacy to dispense a pill. The hope is that with this increased transparency and oversight, PBMs would rein in their behavior.

In 2017, the Senate Finance Committee had written the Creating Transparency to Have Drug Rebates Unlocked (C-THRU) Act which would have accomplished exactly this. Unfortunately, the bill did not make it out of the committee.

Market-based reforms

Several PBMs are emerging that tout their transparency in rebates and spread pricing as their major value proposition. These new PBMs may place some market pressure on existing PBMs to reform their behavior but they all have very little market share so it is going to be an uphill behavior.

Replace spread pricing with pass through pricing

With pass-through pricing, the PBM will stop collecting any spread and thus will charge the payer the same amount they are paying the pharmacy for dispensing a pill. In this case, the PBM will likely start charging a separate administrative fee.

Ban rebates

The proposal gaining the most steam has been to eliminate rebates completely. According to HHS Secretary Alex Azar, “we may need to move toward a system without rebates, where PBMs and drug makers just negotiate fixed price contracts [which are] detached from artificial list prices.”

In November 2020, HHS finalized a rule to effectively eliminate rebates for Medicare Part D plans by reducing protections for rebates under federal anti-kickback laws. These anti-kickback laws prohibit people from getting paid in exchange for the referral of patients in government healthcare programs (e.g. Medicare, Medicaid). Giving PBMs rebates in exchange for formulary placement to channel patients to a drug sounds exactly like the behavior the anti-kickback laws were trying to prevent. However, the “safe harbor” exemption was protecting PBM rebates. This new rule from the HHS would amend the “safe harbor” exemption to no longer protect PBMs serving Medicare Part D patients and thus make it illegal for PBMs to get rebates for Medicare Part D patients.

This rule is supposed to go in effect in 2022 and only impacts Medicare Part D for now. Since the HHS has no authority over private payer plans, they can’t create a rule that would directly affect these commercial payers. However, changes in Medicare do tend to have a ripple effect across the entire ecosystem so we can hope to see more positive changes in the industry as a whole soon.

As much as I like all of these reforms, we have to be careful and tackle the underlying structural factors giving rise to these issues or else the same phenomena — rebates, spread pricing, etc. — but under a different name would emerge. We’ve already seen this problem with rebates, where PBMs have 8+ different revenue streams coming from drug manufacturers that are not called rebates but function essentially the same way.

This points to a larger challenge in healthcare — when most people talk about PBMs and healthcare reforms in general, they tend to talk about it in a simplistic way. “We can easily disintermediate PBMs!” “We just need this one quick-fix, silver-bullet policy change!” The reality is that its much more complicated than that. However, by truly pulling apart the pieces and understanding how our pharmaceutical supply chain emerged, we can examine the deep structural factors behind the surface level problems we see and find the levers that we can pull to make real structural change.

Was this article helpful to you? Do you have any feedback or particular topics that you want me to cover? If so, I would love to hear it! Please comment below or email me at maitreyee.joshi@gmail.com!

Great write-up...definitely forwarding to friends! I know folks who have worked in the industry for decades and still don't fully understand these dynamics.

Great article thank you!